Explorations

in St. Petersburg

Palace Square

Designed as the successor to Moscow's great

imperial squares, this vast formal court is best known as the focal point

of the great political struggles that transformed Russia during the first

decades of the twentieth century.

Designed as the successor to Moscow's great

imperial squares, this vast formal court is best known as the focal point

of the great political struggles that transformed Russia during the first

decades of the twentieth century.

The first of these events was "Bloody Sunday," the catastrophe that initiated the Revolution of 1905. On the morning of Sunday, January 9, 1905, thousands of striking workers, including their wives and children, marched into the square to present a petition for relief to Nicholas II. They were met by soldiers, who began firing on the crowd almost immediately, killing hundreds (according to some accounts thousands) of the demonstrators. The causes of the massacre are disputed, particularly in light of the complicated political tensions in the government at the time. Some historians, for example, argue that both the demonstration and the military reaction were planned by the conservative secret police, who were alarmed by signs that the Tsar had decided upon reform. Whatever its cause, the effect of Bloody Sunday was clear--popular opposition to the Tsar was galvanized, and conservative reactionaries gained strength in the government.

In the wake of Bloody Sunday the country's politics became increasingly divisive, and genuine compromise and reform unlikely. Civil unrest broke out all over the country, and, with the disaster of the Russo-Japanese War, the government was forced to accede to popular demands for reform. It soon became clear, however, that Nicholas and his government had no intention of making good on this agreement. Popular discontent and radical political movements were harshly repressed. While these policies were successful for a time, the government's inept conduct during the First World War created an enormous surge of dissent. The critical turning point came in February of 1917, when the underfed, poorly led, and discontented army refused to act to put down strikes in Moscow and St. Petersburg and called for an end to the war. By March, Nicholas had no choice but to abdicate.

A provisional government assumed control under the leadership of the moderates, first Prince Lvov, then (in July) Aleksandr Kerensky. From its seat in the Winter Palace, the Kerensky government tried and failed to gain popular support and restore civil order. Among the socialist anti-government parties, the radical Bolshevik wing gradually gained strength among the increasingly impatient army and workers. Within a few months the Bolsheviks decided to assume power. On the night of October 26 they staged an armed coup d'etat, storming across the Palace Square and seizing the Provisional Government as it met within the Winter Palace. Although the storming of the Winter Palace was by no means the massive popular uprising that it was to become in the Bolshevik commemorations and in Sergei Eisenstein's film October, it was certainly the moment of symbolic birth of the Soviet state.

The Alexander Column

This towering triumphal column was erected in

1833 as a somewhat belated monument to the defeat of Napoleon in 1812.

Designed by Auguste de Montferrand, who also designed St. Isaac's

Cathedral, the Alexander Column was hewn from the rock face of a cliff in

Karelia over a period of two years, requiring the labors of thousands of

workers. It was then carefully transported to St. Petersburg, taking an

entire year for to complete the transit. On arrival, the monolith was

erected by two thousand veterans of the war. It is surmounted by an angel

of peace, the visage of which bears considerable similarity to Alexander

himself. In keeping with the geometric formality of the Imperial

structures of the city, the Alexander column is positioned so as to align

perfectly with the entrance to the Winter Palace and the triumphal arch

that serves as the entry to the General Staff building opposite.

The

General Staff Building

The

General Staff Building

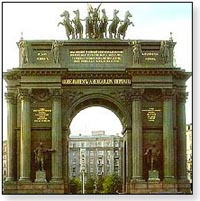

Commissioned by Alexander I in 1819,

the neoclassical General Staff building was situated so as to formally

balance the facing Winter Palace. Its grand triumphal arch was the first

Russian monument to the war against Napoleon. Atop the arch stands a

bronze sculpture of Victory in her six-horsed chariot--in a nicely

lifelike touch, two Roman soldiers restrain the outermost horses, as if to

prevent the team from leaping out onto the square. Although the General

Staff Building is not open to the public, it is in any case of primary

interest for its sweeping, graceful facade.

The Admiralty

The Admiralty building was constructed in 1823

as the administrative headquarters of the Russian Navy. Designed by

Andreyan Zakharov, it is best known for its impressive central tower and

crowning gilt spire. Rising to a height of over seventy meters, the spire

is surmounted by a brilliant windvane in the form of a frigate, which has

become the ubiquitous symbol of the city. The Admiralty's ornate facade is

laden with appropriately nautical sculptures and reliefs, and looks out

over the trees and statues of the pleasant Admiralty Garden.

Decembrists Square

The second of St. Petersburg's great squares

is named for the ill-fated Decembrists' revolt. On December 14, 1825, a

small group of reformist officers entered the square at the head of their

troops in order to prevent the Senate from ratifying the accession of

Nicholas I. Unbeknownst to the officers, the Senators had anticipated such

an action and had already taken their oath to the Tsar in secret. Although

the reformers thus found no Senators in the adjacent Senate building, they

did run into several thousand loyalist troops who had been called into

action by the Tsar. The rebels were attacked, captured, and soon afterward

executed or exiled.

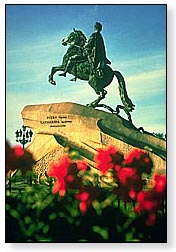

Peter the Great Statue (The Bronze Horseman) Commissioned by Catherine the Great and

sculpted by the Frenchman Etienne Falconet, this striking, dynamic statue

has long been one of the most symbolic monuments in St. Petersburg.

Catherine intended it to glorify the philosophy of enlightened absolutism

that she shared with her predecessor, and for good and bad Falconnet seems

to have succeeded. From different angles the rearing equestrian statue

seems by turns to be benevolent and malevolent, inspiring and terrifying.

In 1833 Pushkin immortalized it in his masterful poem The Bronze Horseman,

in which the statue comes to life to pursue the poor clerk Yevgeny through

the flooded streets of the city. For most of its history, the Bronze

Horseman has been regarded as a symbol of tyranny and destruction.

However, as Russia's Tsarist past has become more distant and somewhat

less politically charged, the statue has come to be appreciated as much

for its dramatic beauty as for its imperial associations.

Commissioned by Catherine the Great and

sculpted by the Frenchman Etienne Falconet, this striking, dynamic statue

has long been one of the most symbolic monuments in St. Petersburg.

Catherine intended it to glorify the philosophy of enlightened absolutism

that she shared with her predecessor, and for good and bad Falconnet seems

to have succeeded. From different angles the rearing equestrian statue

seems by turns to be benevolent and malevolent, inspiring and terrifying.

In 1833 Pushkin immortalized it in his masterful poem The Bronze Horseman,

in which the statue comes to life to pursue the poor clerk Yevgeny through

the flooded streets of the city. For most of its history, the Bronze

Horseman has been regarded as a symbol of tyranny and destruction.

However, as Russia's Tsarist past has become more distant and somewhat

less politically charged, the statue has come to be appreciated as much

for its dramatic beauty as for its imperial associations.

Peter the Great's Cottage

This shockingly modest wooden cottage was

Peter's first residence during his supervision of the construction of St.

Petersburg. Built by army carpenters in a mere three days in the summer of

1703, it contrasts ironically with the grand imperial city planned by its

resident. Although the cottage has been sealed off in a protective brick

enclosure, it still provides both a sense of the city's earliest days and

an oddly intimate glimpse of Peter's character. Unlike many of his

predecessors and his successors, Peter the Great spent a considerable

amount of time trying to act not like a Tsar. At the age of fifteen he

embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe, during which time he studied a number

of crafts and worked in a Dutch shipyard. Even after his return, he

frequently worked incognito among the laborers on his own projects, and it

is likely that he literally lent a hand to the creation of his new

capital.

The Peter & Paul Fortress

Peter's first concern in the creation of St.

Petersburg was with the defense of the approaches of the Neva river delta,

and the Peter and Paul Fortress was the first major building project

undertaken. In fact, it is entirely possible that the idea of building a

new capital city on the site occurred to the young Tsar while he was

living in his cottage and supervising the fortress's construction.

The primary attraction within the fortress is the Peter and Paul Cathedral, begun by Peter as soon as the fortress had been constructed, though not completed until 1733. In keeping with Peter's Eurocentric bias, its design follows the pattern of Dutch ecclesiatical architecture rather than Russian. The most noticeable characteristic of this is the cathedral's tall thin spire, which was designed specifically so as to best Moscow's Ivan the Gret Belltower as the tallest structure in Russia. The cathedral is the resting place of most of the Romanov monarchs (excepting Peter II, Ivan VI, and Nicholas II), and their sarcophagi can be viewed inside.

Engineer's Castle

When Catherine the Great died late in 1796 she

was succeeded by her son Paul, who had been estranged from her for years.

Paul detested his mother, felt uncomfortable ruling in the shadow of her

memory, and may have been more than a little psychologically unsound.

Within a very short while he had alienated his nobility and advisors by

both his erratic, capricious behavior and, more importantly, his attempts

to lessen the power of both the nobility and the military. Having noticed

that he was not exactly revered, Paul became convinced that he was a

target for assassination.

His solution was the Engineer's Castle, a fully-loaded fortress residence, including a broad defensive moat and even a secret escape passageway from the hallway outside of his bedroom. The castle was not without some endearing personal touches, however. As a gesture of defiance at the restrained classical tastes of his deceased mother, Paul had the castle constructed in a kind of postmodern medley of different architectural styles. As a gesture of respect to his own taste, he had his monogram inscribed in the castle thousands of times over. Having rushed the project along, Paul moved in immediately upon its completion in 1801. Whether he believed Engineer's Castle to be impregnable or because he trusted almost no-one, the isolated Tsar brought with him a personal guard of only two Cossacks. Of course, reality quickly lived up to its reputation for irony--Paul was murdered in his bedroom only three days later, having never even reached the hallway.

Exploring

St. Petersburg

Historical Sites | The

Hermitage & The Russian Museum

The Theatres of St. Petersburg | Cathedrals

| Accommodations

Copyright (c) 1996-2005 interKnowledge Corp. All rights reserved.