The Vatnajökull eruption, the ultimate combination of fire and

ice, was a perfect example of the geologic extremes that take place in

Iceland. In the early 1960s, when the United States decided to send men

to the moon, NASA scientists were confronted with the problem of finding

a place on Earth similar enough to the lunar landscape so that the Apollo

astronauts would know what to expect. They needed a terrain that was variegated

and barren, something reminiscent of that "magnificent desolation" that

Neil Armstrong would later describe on July 20, 1969 while the world listened

in astonishment.

"Why not Iceland?" somebody said, "It looks like the moon."

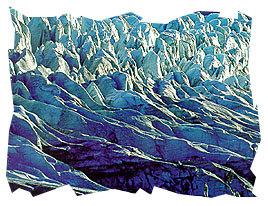

There are certainly places on Iceland that look like they belong on

another world. Rough and empty lavascapes swell up around extinct and active

volcanos. Glaciers carve their way through soft rock, creating serrated

ridges and valleys as defined as cut crystal. There are steaming,

sulfurous blue lakes and geysers that spit up water

like hidden, landlocked whales. At times, the whole country seems like a giant

laboratory in the dreamscape of a sleeping geologist.

But although Iceland may look like another planet, it is, if anything,

more like Earth than Earth itself, a place where mother nature leans towards

the demonstrative.

Why

all the geologic hullabaloo? Well, the island of Iceland sits smack in

the middle of something called the Mid Atlantic Ridge, a 10,000-mile

long crack in the ocean floor caused by the separation of the North American

and Eurasian tectonic plates. Tectonic plates are those rafts of land that

float upon the Earth's molten interior, making up that thin, habitable

crust upon which we live. The plates can do all sorts of things at

places where they meet: they can rub each other as they head in opposite

directions; they can collide head-on in a stalemate, pushing each other

up or down like two fighting rams; or one might win out and push the other

one beneath it. Sometimes, they don't fight at all, but move away from

each other, releasing pressure and exposing the lava sea between them.

The lava bubbles to the surface and cools, forming new land. When this

happens, the area of separation is called a "constructive junction," and

this is precisely what is happening in Iceland. The area is so constructive,

in fact, that 20 million years ago the island didn't even exist.

Why

all the geologic hullabaloo? Well, the island of Iceland sits smack in

the middle of something called the Mid Atlantic Ridge, a 10,000-mile

long crack in the ocean floor caused by the separation of the North American

and Eurasian tectonic plates. Tectonic plates are those rafts of land that

float upon the Earth's molten interior, making up that thin, habitable

crust upon which we live. The plates can do all sorts of things at

places where they meet: they can rub each other as they head in opposite

directions; they can collide head-on in a stalemate, pushing each other

up or down like two fighting rams; or one might win out and push the other

one beneath it. Sometimes, they don't fight at all, but move away from

each other, releasing pressure and exposing the lava sea between them.

The lava bubbles to the surface and cools, forming new land. When this

happens, the area of separation is called a "constructive junction," and

this is precisely what is happening in Iceland. The area is so constructive,

in fact, that 20 million years ago the island didn't even exist.

To get

an idea of the extent of geologic activity, one need only look at Iceland's

volcanos. Over 30 are active, meaning that they have erupted within last

few centuries. On average, Iceland experiences a major volcanic event once

every 5 years, the most active volcano being the picturesque Mount Hekla.

Most of this volcanism takes place along a North-South path down the center

of the iceland, where the Mid Atlantic Rift passes through. The magnitude

of the eruptions varies. Sometimes they do little more than steam and gurgle

up slow-moving lava flows; other times they blast red hot lava thousands

of feet into the air. At numerous times in the island's history, volcanoes

have meant disaster. The largest recorded lava flow in world history happened

here in the late 18th century, when Mount Lakagigar emitted 3 cubic

miles of lava. So much ash was released that the sun was permanently obscured,

and hundreds of thousands of sheep and cattle perished from the poisonous

gasses. In the ensuing famine, one-third of Iceland's people died. More

recently, the important fishing village of Heimaey was nearly destroyed

in 1973 when a volcano called Eldfell erupted virtually inside the town.

Miraculously, two-thirds of Heimaey was saved by using huge jets of water

to cool the lava, which in turn created a rock dam against the flow. Ironically,

by the time the eruption was over, the town's harbor was even better than

before - the new land provided greater protection from wind and water.

To get

an idea of the extent of geologic activity, one need only look at Iceland's

volcanos. Over 30 are active, meaning that they have erupted within last

few centuries. On average, Iceland experiences a major volcanic event once

every 5 years, the most active volcano being the picturesque Mount Hekla.

Most of this volcanism takes place along a North-South path down the center

of the iceland, where the Mid Atlantic Rift passes through. The magnitude

of the eruptions varies. Sometimes they do little more than steam and gurgle

up slow-moving lava flows; other times they blast red hot lava thousands

of feet into the air. At numerous times in the island's history, volcanoes

have meant disaster. The largest recorded lava flow in world history happened

here in the late 18th century, when Mount Lakagigar emitted 3 cubic

miles of lava. So much ash was released that the sun was permanently obscured,

and hundreds of thousands of sheep and cattle perished from the poisonous

gasses. In the ensuing famine, one-third of Iceland's people died. More

recently, the important fishing village of Heimaey was nearly destroyed

in 1973 when a volcano called Eldfell erupted virtually inside the town.

Miraculously, two-thirds of Heimaey was saved by using huge jets of water

to cool the lava, which in turn created a rock dam against the flow. Ironically,

by the time the eruption was over, the town's harbor was even better than

before - the new land provided greater protection from wind and water.

It may be fire

that created Iceland, but what shapes it is ice. Ten thousand years ago,

the entire island was covered by ice, and the creeping, cutting glaciers

are responsible for Iceland's extraordinary fjords and valleys. Today,

a full 11 percent of the island is buried beneath ice caps, but the modern

glaciers are believed to be relatively new; they probably formed around

500 BC and are still increasing. The largest glacier, Vatnajokull,

is 3,200 feet thick and 3,200 square miles in area. It is not only

the largest glacier in Europe, but larger than all of Europe's other glaciers

combined.

It may be fire

that created Iceland, but what shapes it is ice. Ten thousand years ago,

the entire island was covered by ice, and the creeping, cutting glaciers

are responsible for Iceland's extraordinary fjords and valleys. Today,

a full 11 percent of the island is buried beneath ice caps, but the modern

glaciers are believed to be relatively new; they probably formed around

500 BC and are still increasing. The largest glacier, Vatnajokull,

is 3,200 feet thick and 3,200 square miles in area. It is not only

the largest glacier in Europe, but larger than all of Europe's other glaciers

combined.